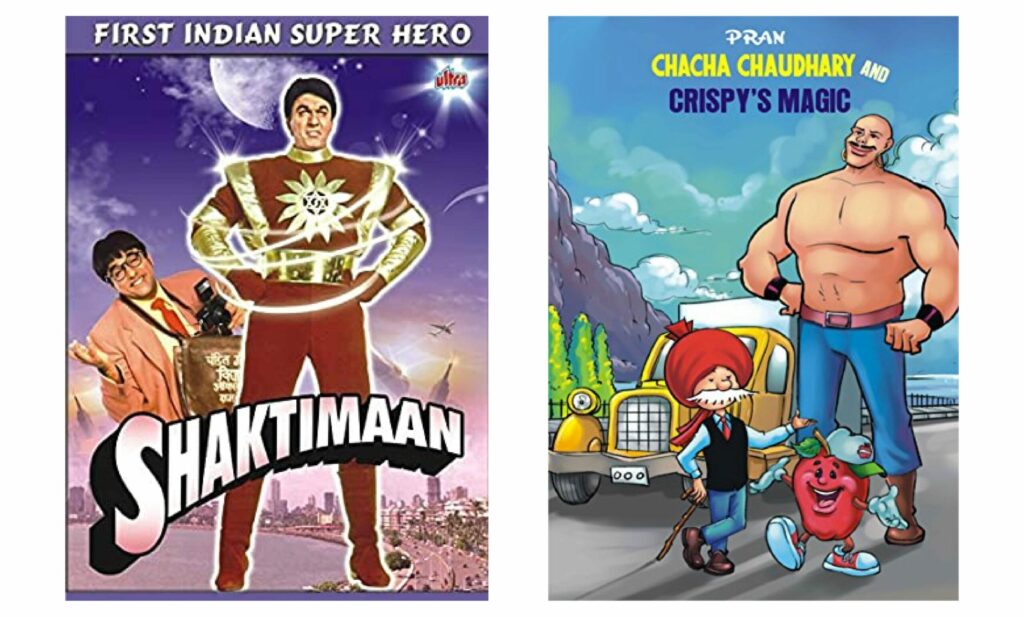

From Chacha Chaudhary to Shaktiman: Can Fictional Character Be Protected Under Law of Copyright?

If you are a Binge watcher or Serioholic or even if loved to spend your free time before TV Shows, then you must remember that seven years ago in 2013 the owner of the TV show “Comedy Night with Kapil Sharma” has claimed sole, exclusive, absolute and unlimited ownership over character “Gutthi” from the show coming out on Colors TV. Recently, Activision- the publisher of popular video game Call of Duty (COD) was sued over their COD character Mara for copyright infringement. Along with these two examples, there are many other cases that raise questions that whether the fictional characters like Chacha Chaudhary, Byomkesh Bakshi or Shaktiman can be protected under the Law of Copyright. Through this article, an attempt was made to elucidate all possible protection of fictional character under the law of copyright.

Introduction to Law of Copyright

Copyright is the bundle of rights that confers an exclusive right upon the author of the original work. It is intended to protect the idea which is expressed in some tangible form, but not the idea itself. The work commonly protected by copyright includes literary, artistic, musical, dramatic, sound recording, and cinematograph film.

Possibilities of Copyright Protection for Fictional Character

In India, Section 13 of the Copyright Act, 1957 provides subject matter or work in which copyright can subsist. If we try to understand Section 13 in the light of the fictional character we can draw a conclusion that the fictional character might be protected under the category of literary or dramatic work if we consider it as part of a script or it can be protected as a performer’s rights.

For a while if we assume that these are the two conditions in which fictional character can get protection, then arise a conflict of authorship/ownership between the person who has created the character and the person who is living the character. Since the person who has created the character including the name and appearance will be entitled to copyright protection under the literary or dramatic work, and on the other hand, the person who is living the character before the television through its personality traits and voice is entitled to performer right. To avoid such conflicts it is necessary to provide a separate clause in the Copyright Act for the protection of the fictional character or an illustration explaining the category in which it will fall.

Judicial Pronouncement

In the absence of any explicit provision under the Law of Copyright, Indian Court has developed some precedent that will help us further in understanding this topic. The first and foremost case which can elucidate the whole scenario will be Star India Private Limited vs. Leo Burnett, 2003 (2) Bom CR 655, 2003 (27) PTC 81 Bom. wherein, the creator of the fictional character of TV Series “Kyun Ki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi” tried to prevent telecast of commercial advertisement film titled “Kyun Ki Bahu Bhi Kabhi Saas Banegi” featuring characters who were identical to the Plaintiff’s television series. After reviewing the evidence, the Hon’ble Court denied the Plaintiff’s request for relief and establishes a test of public recognition for determining character rights.

Again in the case of Arbaaz Khan vs. NorthStar Entertainment Private Limited, 2016 SCC OnLine Bom 1812 : (2016) 3 AIR Bom R 467 it was argued by the plaintiff that the defendant has portrayed the character of “Chulbul Pandey” from the “Dabangg” franchise in their movie. The court rejected the plaintiff’s contention and refused to grant an injunction. The court ruled point-wise dissimilarity test to compare the fictional character. Though the court has refused to grant an injunction, they have admitted that the fictional character is capable of receiving legal protection in India.

Earlier in the case of Raja Pocket Books vs. Radha Pocket Books, 1997 (40) DRJ 791 the plaintiff got the relief against the imitation of their fictional character “Nagrajby the defendant through their fictional character in the comic series “Nagesh”.

Foreign case studies of similar nature

In the United States the subject matter is far more evolved, with elaborate judicial tests. For instance in the famous case of Walt Disney vs. Air Pirates, 581 F.2d 751 (9th Cir. 1978) the Federal Circuit Court of United States has evolved two-step test for determining the infringement of characters. It can summarize as follows:

- First Step: Comparison of the Visual Similarities

- Second Step: Comparison of the Personality of the Character

In another case, Nicols vs. Universal Pictures Corporation, [45 F.2d 119 (2d Cir.1930)] the court has evolved the “Character Delineation Test” that means only such character can be entitled to the copyright protection that has developed to such extent that it may be delineated from the story itself.

Further in another case of Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. vs. Columbia Broadcasting System, [216 F.2d 945 (9th Cir. 1954)] the court has developed “The Story Being Told Test” where it was held that for the copyright protection the story must revolve around the character itself only.

Concluding Remark

From the above discussion it is clear that fictional character can only be protected through the law of Copyright. They can either be protected under literary, dramatic work or through performer’s right. The Copyright Act does not specifically recognize a fictional character as a copyrightable ‘work,’ nor does it identify it as a subset of any of the copyrightable ‘works’, which makes it difficult to protect a fictional character under the copyright law.

Though the judicial pronouncement to some extent has shown their interest to protect the fictional character. Whether it is “Chulbul Pandey” of the Dabangg franchise or “Nagraj” of the comic series, both these cases have contributed greatly to the protection of the fiction character. Since it cannot be denied that current copyright law is inadequate to protect these fictional characters, and thus it would do more harm to the author or creator of these fictional characters. For now, we can only hope that policy-makers will discuss this topic soon and bring put some provisions for the protection of fictional characters.